Notes

La madera en el arte taino de Cuba

Created by Miguel Sague Jr Aug 22, 2024 at 2:46am. Last updated by Miguel Sague Jr May 5, 2025.

AKWESASNE NOTES history

Created by Miguel Sague Jr Jun 12, 2023 at 4:15pm. Last updated by Miguel Sague Jr Jun 12, 2023.

registration form art all night Pittsburgh

Created by Miguel Sague Jr Apr 17, 2023 at 10:58am. Last updated by Miguel Sague Jr Apr 17, 2023.

Events

Digging Sticks And Stone Hoops

Archaeologists excavating ancient Indigenous sites in the Caribbean region have long wondered what was the meaning and purpose of the enigmatic "stone collars" that have been discovered at several places in the region. These are highly polished sculpted stone objects shaped like oval hoops.

The use of digging sticks for the cultivation of the soil is a widespread custom among native peoples all over South America. There is evidence that many tribes who engaged in the agriculture of tuber roots such as the potato of the Andean Incas and the yuca of the Amazonian Arawaks utilized digging sticks with foot rests that allowed greater force to be applied to the tool via the use of the leg muscles.

We believe that the ancestors of the Taino used two kinds of digging sticks, one with a foot rest and the other without. Today only the digging stick without the foot rest survives in the peasant farmlands of Cuba and still goes by the ancient Taino name of “coa”. However, modern Andean farmers still use the foot rest type of digging stick in the highlands of Peru.

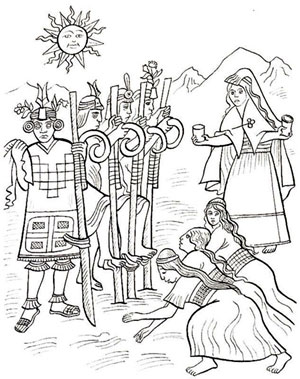

Drawings of Inca farmers using “foot-rest” type of digging sticks in the fields of ancient Peru.

modern-day Andean farmers using the foot-rest digging-stick, sometimes referred to as a "foot-plow"

Primitive coas were easily crafted out of wood by the Tainos quite early in their history. A wooden coa of the “foot-rest” variety could be conceivably fashioned out of a long straight branch of a hardwood tree. A lower branch of this limb could be shaped into the foot rest and the portion that originaly attached to the main trunk of the tree could have been pointed and fire-hardened as the digging end.

The Taino inclination for decoration very probably prompted the carving of the area closest to the digging point where the thickened crook of the branch remained.

It is evident that the end of the “foot-rest” was decorated with the image of a snakes head. The Tainos associated farming with the fertility of the Mother Spirit Ata Bey and she appears to have been associated with this reptile.

The archelogical author Eugenio Fernadez Mendez (Fernandez-Mendez 1972) maintained that the Tainos associated the Taino Mother spirit (whom he identified as Ata Bey and Gua ban Ce) with the image of the snake. He also maintained that the so-called “stone collars” were actually representations of the maternal snake spirit, an allegorical “serpent” as a result of the similarity in shape and form. The coa also was such a sacred serpent which allowed to peek into the inner reaches of the Mother Spirit’s womb every time the Taino farmer pushed his or her foot down on the foot-rest and the coa was buried into the soil. The coa was used as a kind of messenger to the inner Earth Mother to plea to her on behalf of the farmer for good crops.

The Tainos, no doubt, found a way to ritualize the long snake-like shape of the coa further by taking ceremonial, non-utilitarian wooden coas and soaking them until it was possible to start bending them. This action allowed the Tainos to make the shape of the agricultural instrument more “snake-like” by turning it into an image of a coiled serpent. The end of the long pole was then tied to the foot-rest to create the characteristic ovoid shape that is familiar to anyone who has seen the famous Antillean “stone collars”.

As they often did, the Tainos adapted this wooden image to their other favorite art medium, stone. Obviously the stone pieces are the ones that most easily survived the ravages of time and Spanish Inquisitonal destruction.

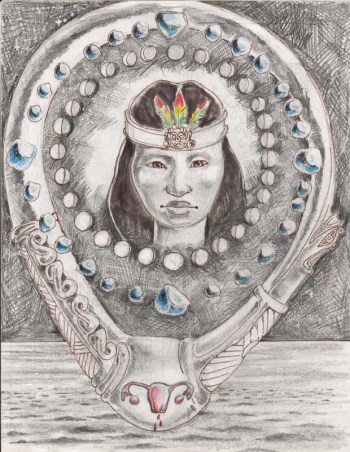

The ritual oval-shaped coa-hoop not only represents the coiled sacred serpent but also the pear-shaped outline of a human uterus. It is the image of Ata Bey’s all-creative womb and the reflection of the circle created by the 28-day menstrual cycle. It is the imagery that comes to mind when one thinks of the moon “Karaya” and its allegorical link between the human woman and the Divine woman.

The ritual oval-shaped coa-hoop not only represents the coiled sacred serpent but also the pear-shaped outline of a human uterus. It is the image of Ata Bey’s all-creative womb and the reflection of the circle created by the 28-day menstrual cycle. It is the imagery that comes to mind when one thinks of the moon “Karaya” and its allegorical link between the human woman and the Divine woman.

A number of scholars have suggested that the ancient Tainos used the stone hoops as a kind of ceremonial support for the equally famous three-pointed stone carvings known popularly as "three-point cemi". They conjecture that the three-pointers were actually tied to the stone hoops with twine or cords either inside or outside the hoop.

This photo depicts an actual ancient stone hoop that is part of the collection at the Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian. As you can see, the curators at the museum maintain a three-point cemi tied to the hoop to represent what we now know of the ancient Taino tradition surrounding these two objects.

We in the Caney Circle have arrived at the conclusion that this assessment is correct. The ancient Taino did, in fact, tie three point cemi sculptures to the stone hoops. The reason they did this is because this tying ritual represents the ceremonial attachment of one entity with the other. Some of the three point cemies actually represent Yokahu, the Lord of the Life Force in a "dead" or "dormant" manifestation, his bare ribs and spinal vertebrae showing and his decapitated head resting between his arms.

We believe this graphic representation of the Life Spirit as a dead entity is purposely designed to indicate the fact that our ancestors understood this spiritual character to have a life cycle just like any other living thing especially food crop plants. Within that life cycle he is born each Spring, he rises to full maturity in the Summer, then wanes, grows aged and dies at harvest time in the Fall season when the mature crop plants are pulled out of the ground and killed. Yokahu is a spiritual entity that represents living things especially plants. His name is derived from the name of the most important crop plant of the ancient Tainos, the yuca plant, Yuca-hu, Yokahu.

We maintain that the tradition also included the belief that the soul of the dead Yokahu traveled down into the primordial underworld back to the womb of his mother Atabey during the Autumn season, where it would be re-attached to the mystical uterus of the Earth Mother on the first day of Winter in December and then gestate there for three months until it could be born again at Spring Equinox on March 21st.

The act of re-attachment that took place between the soul of the dead Yokahu and the divine uterus in December at Winter Solstice was ceremonially re-enacted by our ancestors by tying the three-point cemi sculpture that represented the dormant Life spirit's soul to the oval-shaped stone hoop that represented the womb of his mother. We in the Caney Circle now have re-ignited that tradition by actually tying a three point cemi sculpture that represents Yokahu's soul to an oval-shaped hoop that represents his mother's womb every Winter Solstice just as our ancestors did. This moment symbolizes the defeat of death and despair itself.

After allowing these two objects to remain tied to each other for three months we then feature them again in another ceremony on the day of Spring Equinox in March. On that day we untie the two sacred objects and separate them, symbolizing the re-birth of Yokahu when the divinity is separated from his mother's womb.

This is how we represent the victorious return of the Lord of Life back to the realm of the living. This is not just the victory of the spirit of Life and hope after he defeats death and despair on the day of Spring Equinox, it is also a victory for his mother, whose power of creation allows her to provide the gift of Life to the world from her own womb. It is a profound symbol of her generosity as she provides the world with yet another year of food sustenance.

© 2026 Created by Network Financial Administration.

Powered by

![]()

You need to be a member of Indigenous Caribbean Network to add comments!

Join Indigenous Caribbean Network